Charlotte Buresova

1983-1904

Charlotte Buresova was a Jewish artist born in Prague on November 4, 1904, the only daughter of a tailor. At a young age she showed signs of artistic talent and her family saw to it that she received an extensive education, including painting, the piano and French. After studying with private tutors, she attended the Industrial Art School for three years, and then studied for a further three years at the Prague Academy of Art, until 1925. Her paintings were mainly figurative and classical in style. She painted portraits, still lifes and flowers, but did not exhibit her works, instead giving them to friends as gifts. Buresova married young to a non-Jewish lawyer and gave birth to a son. When the Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia, she divorced her husband in order to prevent the decrees against Jews from affecting her family.

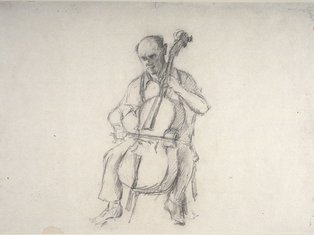

In 1941 Charlotte Buresova was forced to leave her home, which had been confiscated by the Nazis. In July 1942 she was imprisoned in Terezin camp and put to work in the Sonderwerkstätte (special workshop), where she painted roof tiles for the Germans. Later she was sent to the artists' workshop. At the order of the Germans she painted copies of classical masterpieces like those of Rubens and Rembrandt. Her own works were done in pencil, crayon, chalk, watercolours and a few oils. The subjects of her paintings, some of which depicted the extensive artistic-cultural activity in Terezin, included portraits of children, musician friends like Gideon Klein and Otto Karas-Kaufmann, flowers and dancers. Buresova said that she wanted to give her depictions of dancers a grace and beauty to counter the terror, hunger and suffering everyone suffered from.

According to Buresova there were different points of view among the artists in Terezin. The Dutch artist Jo Spier believed that artists must paint even when cannons were firing. Buresova disagreed, insisting that there were times when she could no longer create. But Spier would push her, encouraging her not to give in but to continue creating. She would later say that of all her art works those produced in Terezin were the most frank and direct because she was able to work independently.

Her situation in Terezin was better than that of most of the other inmates. She worked all the time, had a room of her own, possessed books and was in touch with her friends. She said that since her family were not with her she had less concerns than other inmates - like her fellow artist Otto Ungar, who constantly worried about food for his family. In an interview with Miriam Novitch, the first curator of Beit Lohamei Haghetaot (the Ghetto Fighters' House Museum) and the person who laid the foundation for its rich art collection, Buresova said that "what was more terrible than hunger and indecent housing was the unknown tomorrow." She was terrified of the deportations to the East "since no one knew who would go next."

A Nazi officer, who was very impressed by her artistic talent, prevented her deportation. He asked her to paint the Holy Mother. Buresova painted the Madonna with a very realistic tear in her eye and when the officer saw it he was so impressed that he said to her: "Never complete the painting. As long as you are working on it, you will not be deported to the East."

Three days before the liberation of Terezin, Buresova, along with a small number of inmates, succeeded in escaping and returning to Prague in the Swedish ambassador's car.

Charlotte Buresova lived in Prague until her death in 1983. Her son, a doctor, still lives there. Some of the works she produced after the war were based on her memories of Terezin.

Buresova donated some of her works from Terezin to the art collection of Beit Lohamei Haghetaot (the Ghetto Fighters' House Museum).

(Dr Pnina Rosenberg)

References

Beit Thereseinstadt (Thereseinstadt House) archive, Givat Haim-Ihud, Israel.

Janet Blater and Sybil Milton. Art of the Holocaust. Pan Books, London, 1982.

Mary S. Constanza. Living Witness: Art in the Concentration Camps and Ghettos. The Free Press, New York, 1982.

Miriam Novitch, Spiritual Resistance: Art from Concentration Camps 1940-1945 - A selection of drawings and paintings from the collection of Kibbutz Lohamei Haghetaot. Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981.

Sabine Zeitoun and Dominique Foucher (editors). La masque de la barbarie: le ghetto de Thereseinstadt 1941-1945. Preface by Milan Kunda. Centre d'Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Ville de Lyon, 1998.

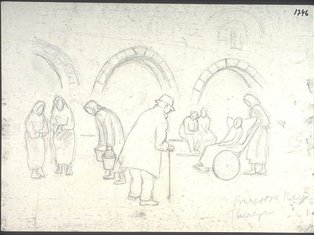

Pencil on paper, 33 x 45 cm

Signed: Buresova (Czech) Terezin

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1746.

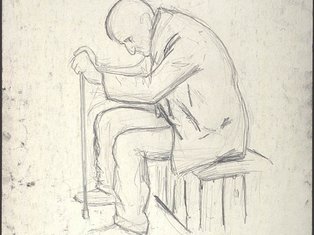

Pencil on paper, 33 x 45 cm

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1748.

Donated by the artist

Pencil on paper, 33 x 45 cm

Signed: Buresova (Czech) Terezin

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1749.

Donated by the artist

Pencil on paper, 33 x 45 cm

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1752.

Donated by the artist

Pencil on paper, 33 x 45 cm

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1746.

Donated by the artist

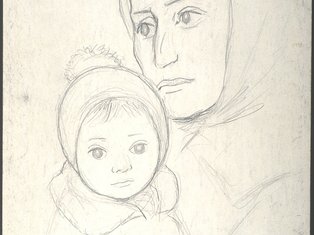

Pencil on paper, 45 x 33 cm

Signed and inscribed, lower middle: Charlotte Buresova (Czekosl), Mother + Child in Terezin

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1755.

Donated by the artist

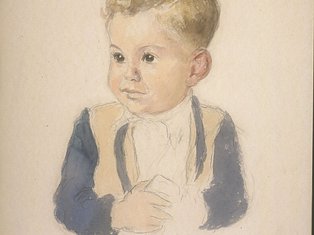

Watercolor and pencil on paper, 29 x 19.5 cm

On the reverse are two sketches of an old man: one seated; the other standing.

Signed and dated on reverse, lower right: Ch. Buresova, '43

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1737.

Donated by the artist

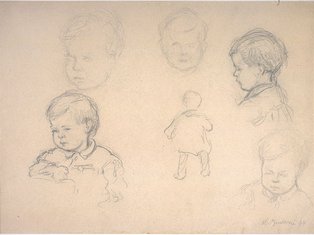

Pencil on paper, 31 x 42.3 cm

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1011.

Donated by the artist

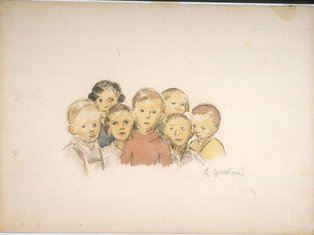

Pencil on paper, 33 x 45 cm

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1007.

Donated by the artist

Pencil on paper, 33 x 45 cm

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1008.

Donated by the artist

Pencil on paper, 33 x 45 cm

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1001.

Donated by the artist

Pencil on paper, 33 x 45 cm

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Museum Number 1739.

Donated by the artist