Jacques Ochs

1883-1971

Jacques Ochs was born in Nice (France) in 1883, to a Protestant family. They moved to Liège (Belgium) in 1893 where Ochs studied art at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Liège (graduating 1903). Afterwards, he continued his studies at the Académie Julian in Paris (until 1905).

Ochs volunteered for the army in World War I and was seriously injured in an air attack. In 1920 he became a lecturer in painting at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Liège, and in 1934 he was appointed to be the curator of the city's Musée des Beaux Arts. Ochs was a man of many talents; in addition to being a gifted artist he was an Olympic fencing champion, and a caricaturist, who published his works in various newspapers including the French daily, Le Figaro, and a satirical magazine published in Brussels called Pourquoi Pas?. In early April 1938, he depicted Hitler on the cover of Pourquoi Pas? with a swastika on his head and a sceptre in he form of a headless Jew. An artist with right-wing tendencies who envied Ochs' success informed on him and Ochs was arrested at the academy in Liège, on 17 November 1940.

A month later, on 17 December, Ochs was imprisoned in Breendonk camp, to the south of Antwerp. Since 20th September, Breendonk had been used as a police internment camp holding mostly political prisoners and foreign Jews. Ochs used caricature to document the life there, drawing portraits of his fellow inmates on paper. When the commandant, Philip Schmitt, who was very proud of "his" camp, became aware of Ochs' artistic talents, he ordered him to make him drawings of the camp and its inmates - a gallery of victims. Among them was a portrait of Alter Breziner, Antwerp's shochet (Jewish ritual slaughterer). Immediately after his arrival, Breziner's hair had been shaved off and he looked humiliated. Ochs was obliged to obey the demands of the SS, but tried to ease the suffering of his fellow inmates. He would drag out their portrait "sittings" to provide them with as much rest as possible. Professor Paul Lévy, who today serves as the president of the Mémorial National du Fort de Breendonk, and was interned with Ochs, has said that although the inmates did not have mirrors, they knew what they looked like through Ochs' works.

A Flemish SS man who had known Ochs previously succeeded in smuggling him out of the camp in February 1942. This same man was also able to smuggle out some of the drawings Ochs had made for commandant Schmitt.

After a while, Ochs was interned again, along with his sister, in Malines camp. He continued to draw and managed to avoid deportation through a "medical" opinion confirming had been baptised as a Protestant, and so could not be Jewish. He was liberated from the camp by the British forces.

Ochs' works produced under the orders Schmitt are a moving testimony by a sensitive and talented artist, depicting and sharing in the suffering of his comrades, who were forced to be his models. Only a small number of the characters he drew survived. After the war, Ochs used his drawings to reconstruct scenes from the camp. He published these in 1947, in a book called Breendonck - Bagnards et Bourreaux [Breendonck - Slave Laborers and Hangmen].

SS-Sturmbannführer Schmitt, the commandant of Breendonck camp and, later, of Malines, was tried in Antwerpen in 1950 and sentenced to death. He was the only SS man sentenced in Belgium, and his was the last execution before the country abolished the death penalty.

After the war, Jacques Ochs went back to work as a lecturer in the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts and even though his sight had been damaged during his internment, he continued to paint and draw. In 1948 he became a member of the Académie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Arts de Belgique [The Royal Academy of Science, Literature and Art in Belgium] and a member of the Commission d'Achat des Musées Royaux d'Art Moderne [Acquisitions Commission of the Royal Museums of Modern Art].

He exhibited in many exhibitions, among them group exhibitions of the "Cercle des Beaux-Arts", and a retrospective exhibition was also held for him. Ochs received many awards in recognition of his artistic talents, among them a gold medal at the second Biennale in Menton [Médaille d'or de la deuxième Biennale de Menton] in 1953 and a gold medal for art, science and letters in Paris [Médaille d'or des Arts, Sciences et Lettres, Paris] in 1959. He passed away in Liège in 1971.

A number of his drawings from Malines were donated to the art collection of Beit Lohamei Haghetaot (the Ghetto Fighters' House Museum) by Irène Awret, who was interned with him in this camp.

(Dr Pnina Rosenberg)

References

Irène Awret's Testimony, Ghetto Fighters' House, no date.

Breendonck – Bagnardes et Bourreaux, text et dessins de Jacques Ochs. Editions du Nord, Albert Parmentier, Bruxelles, 1947

Paul M.G. Lévy. "Jacques Ochs à Breendonk", in The Memory of Auschwitz in Contemporary Art – Proceedings of the International Conference. Brussels, 11-13 December 1997, published as Bulletin trimesterial de la Fondation Auschwitz, no. 60 (July-September) 1998, pp. 41-44.

Miriam Novitch. Spiritual Resistance: Art from Concentration Camps 1940-1945 - A selection of drawings and paintings from the collection of Kibbutz Lohamei Haghetaot. Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981.

Jacques Ochs – Retrospective. Musée d'art Wallon, Liége, 1975.

Pierre Somville, Marie-Christine and Gilbert Depouhon. Le Cercle royal des Beaux-Arts de Liége 1892-1992. Bruxelles, 1992.

Letter from Professor Paul M.G. Lévy, President, Mémorial National du Fort de Breendonk, October 2000.

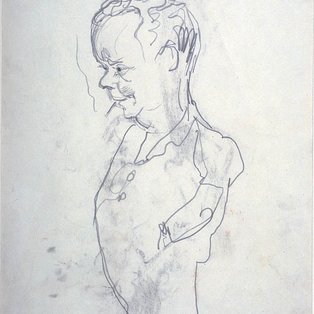

![Portrait of the SS Guard "Ferdkopf" [Horse Head] Malines Camp 1944 Portrait of the SS Guard "Ferdkopf" [Horse Head] Malines Camp 1944](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/6/csm_LG0068X_87113390bb.jpg)

Signed and inscribed (in German), upper right: Jacques Oks, "S.S. Ferdkop". Dated, lower right: Malines 1944

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot

Museum Number 144

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot

Museum Number 145.

Donated by Irène Awret

On the reverse is a portrait of Diego Meier.

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot

Museum Number 2085.

Donated by Irène Awret

On the reverse is a portrait by Irène Awret

© Beit Lohamei Haghetaot

Museum Number 123.

Donated by Irène Awret