Leo Haas

1901–1983

Leo Haas was born in Opava, Czechoslovakia to parents of Slovakian origin. He was the oldest of four children. His artistic abilities were fostered from an early age - he studied piano and voice in addition to painting, a talent he inherited from his grandfather, a church muralist. His art teacher recommended that he continue to study art and to do so he moved to Karlsruhe in Germany, attending the art academy there. His first year of studies was financed by a rich relative from the United States, but when the relative died Haas had to support himself as a musician in bars or restaurants. Haas produced paintings and lithographs depicting these scenes - artistic subjects that were common at that time.

In 1921 Haas moved to Berlin where he continued his studies at the school for decorative arts. He studied with Emil Orlik, who made him his assistant. As in the past, Haas continued to earn his living from playing in cafes and from the sale of his works - primarily watercolor miniatures. In 1922 he became assistant in a graphic design studio and from then on his main source of income was from painting.

Haas was regarded as belonging to the expressionist stream which included artists like Max Liebermann and Kathe Kollwitz. He was inspired by artists of the past like Goya and Toulouse-Lautrec. In 1923 he travelled to France - first to Paris and then Albi, Toulouse-Lautrec's birthplace, where he studied the artist's works in the local museum. From there he moved to Arles, in the steps of Van Gogh. His last stop before returning home to Opava was Marseilles.

In 1924 Haas tried his luck as a journal caricaturist in Vienna. During his two years there he helped establish, and became an integral part of, the local Bohemian community. In 1926 he returned to Opava, working in advertising and as a set designer for a theatre troupe that performed throughout Moravia.

In 1929 he married Sophie Hermann and became a well-known portrait painter in Opava, earning enough money to support his family and even help out his parents. Haas, who had acquired a reputation as a versatile artist, worked on behalf of Czech-German artistic cooperation within the Association of German Artists. In 1935, when the National Socialist party came to power, Haas abandoned his activity with this association and became the director of a small printing house.

The first pogrom in Opava took place in 1937. Haas's works were designated as "degenerate art" and he was accused of cultural Bolshevism because of the caricatures he had published. After the Kristallnacht (the first major attack on Jews) in November 1938, he and his wife went to live with her parents in Ostrava.

On 15 March 1939, Moravia and Bohemia were occupied by the Nazis and the Nüremberg race laws and other anti-Jewish laws were put into effect. As a result, Jews lost their jobs and property. In October 1939, after the outbreak of war with Poland, Austrian Jewish men between the ages of 16-60 were gathered together at the railway station. Thousands of them were sent to Nisko near Lublin, where the transports were sorted according to professions and were employed building wooden barricades and fences around the camp. In Nisko, Haas was employed as a wagon driver bringing food and construction materials from Lublin, and also as a tailor's and shoemaker's apprentice.

While in Nisko, Haas painted portraits of SS soldiers, for which he received better food and art materials. He was also able to move freely around the camp, which enabled him to draw the building sites, portraits of his comrades, transports arriving and leaving, and the general life of the camp. More than a hundred works from that period have survived and they provide important documentation for this concentration camp in Poland.

When the camp was dismantled many of the internees fled to the other side of the Saan River which was controlled by the Russian army. Haas returned to Ostrava where he separated from his wife Sophie who wanted to flee further. Haas, however, refused to abandon his father and sister. He worked at hard physical labor (cleaning and renovating sewers) - work organized by the Jewish community. While there he met Erna Davidovitc, the woman who would become his second wife. Her family assisted in the illegal smuggling of residents to Poland, an activity which Haas himself took part in after the death of his father in 1941. Haas was arrested by the Gestapo in August 1942 but was released from the Ostrava prison through the help of the Jewish community. But this ensured that he would be included in the next transport to Terezin, which left at the end of September 1942.

On 1 October 1942 Haas and his extended family (his wife, her parents, and his sister, Elvina) arrived at Terezin, where they were forced to separate. This was a very difficult time in Terezin. With many transports arriving from Germany and Austria, the number of internees reached 60,000, including thousands of elderly people. The increased numbers made life much harder: food portions became smaller; sanitary and hygienic conditions deteriorated; and there were many deadly diseases (more than 15,000 people died in Terezin by the end of that year).

At first Haas was put with the group of prisoners that transported building materials for the railway tracks. Thanks to Yakov Edelstein, of whom Haas had made a portrait, Haas was transferred to the Zeichenstube (technical-graphic department) of the camp. The department's job, among others, was to organize the construction of the railway line that ran through the camp. Several other famous artists worked in the Zeichenstube, among them Otto Ungar, Ferdinand Bloch and Bedrich Fritta. Fritta headed the team and became a close friend of Haas.

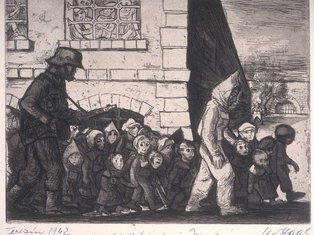

Haas drew portraits of his colleagues. He also gave painting courses for the children of the ghetto, for which he received a little food. He used this to prepare original meals that became famous among his circle.

Work in the graphic department enabled its employees to visit other parts of the ghetto. Haas used this to make frequent visits to his wife, who lived in a different section. He also used the opportunity, like his colleagues, to make drawings documenting ghetto life. He had to do these in secret in an attic or while hidden among thousands of prisoners in case the SS discovered this forbidden activity. He depicted many subjects: searching for food, people waiting to be transported, the transfer of internees from one dwelling place to another, the buildings, portraits of inmates, sketches of the elderly, the sick, the dying, and the dead. Haas, Fritta and Ungar would often meet in the evening to work on their drawings. Collectively, they created a large body of work illustrating all aspects of life in Terezin.

On 23 June 1944 a delegation of the Red Cross visited Terezin in order to see the ghetto and its living conditions. Prior to this the Nazis initiated a beautification program - to camouflage the true conditions in the ghetto. The streets were given names; gardens were prepared, with well-tended lawns; a kindergarten was set up; and 7,500 elderly and sick people were transported from the camp on their last journey, so that Terezin might look like a "healthy" place. The staff of the technical department were recruited for this campaign - they made false fronts for shops which would not be used after the visit, and they prettified and decorated the ghetto according to the Nazi's instructions.

To avoid the truth being revealed, the Nazis began to search through the tools of the people in the technical department, who had to find hiding places for their works. Fritta buried his in the ground inside a metal box; Ungar hid his paintings in a depression in a wall; and Haas hid his in an attic. The Nazis also searched the art dealer, Leo Strauss. Strauss had used his "Aryan" family and close connections with the ghetto's Czech police to smuggle the artists' documentary works outside the borders of the Reich - probably to Switzerland. He had done so in the hope that this might rouse public opinion, or at least testify to what had occurred, even if the artists themselves failed to survive.

Several days before the visit, the artists were warned by a co-worker in the technical department, a member of the Ältestenrat (Council of Elders), that they would be called in for interrogation the next day. Ungar, Fritta, Haas and Bloch were brought to the main headquarters where they were interrogated by Adolf Eichmann. Eichmann was determined to discover who among them had created the smuggled works and who their contacts were with the outside world. The artists were taken to an underground cell where they found the art dealer, who had been imprisoned several days earlier. They maintained their silence and, after a difficult interrogation, were sent to the Gestapo prison which was in the "Small Fortress" of Terezin. The artists' families were also sent to the fortress - their wives, Ungar's five-year old daughter Susanna, and Fritta's three-year old son, Thomas.

Haas was imprisoned for three and a half months. During this time he and the other artists were employed constructing railway lines and doing other hard physical labor. Many died doing this work and Haas himself was seriously injured in the leg. He was operated on by Dr Pavel Wroclaw, using improvised means. Haas recovered, due in large part to extra food given to him by the person in charge of Czech prisoners. This man even hid Haas in his cell, but Haas was discovered and put into solitary confinement for eight days without food - though his friends succeeded in smuggling in a little.

On 25 October 1944 Haas and Fritta were called to the offices of the main headquarters, where they were accused of distributing atrocity propaganda to outside countries. As a result, both artists were sent to Auschwitz, on the way being removed from the train at Dresden for additional interrogation. Haas arrived in Auschwitz on 28 October and was classified as a political prisoner with the number 199885. Fritta also arrived in the concentration camp, fell seriously ill with dysentery and despite treatment by Dr Wroclaw, who was also a prisoner in the camp, he died of blood poisoning eight days later.

Haas's artistic talent came in handy in Auschwitz. He was given an administrative position in Block 24 where he produced sketches for Dr Mengele. Three weeks later, Haas, along with another Czech artist, were called to the Elders' Block and asked to copy something from a fashion magazine. Then, in November 1944, Haas, other artists and a number of chemists from Belgium, were transferred to Sachsenhausen camp where Haas was given a new number: 118029. After a few days the group were sent to blocks 18 and 19, which were separated from the rest of the camp by an electrified barbed-wire fence. There they were given their mission: they would join a "counterfeiting gang" who had already been at work for two years producing counterfeit British currency, documents and stamps. Haas' group was given the job of counterfeiting American money.

At the end of February 1945, the members of the group were ordered to load their equipment onto a railroad car and, along with other prisoners, were transferred to Mauthausen via Dresden and Prague. In this camp they were kept in the notorious Block 20. Three weeks before their arrival, 700 Russians had been murdered there. The members of the group now feared for their lives. The counterfeiting stopped, their counterfeit products were taken by the SS, and instead they were given construction. On 5 May 1945 the prisoners were transferred to Ebensee camp, where they were liberated the next day by the Allied forces.

After his liberation Haas returned to Terezin and there, in the Magdebourg Barracks, he found his entire art collection, as well as many works produced by Fritta. Haas learned that most of his friends and family had perished: Ungar had been transported to Auschwitz and perished during the Death March to Buchenwald; Bloch had been beaten to death in the Small Fortress (October 1944); and Fritta's wife Johanna had died in Terezin in February 1945. Frida Ungar and her daughter had survived, as had Thomas Fritta. Haas's wife Erna had also survived but was in very poor health. The couple adopted Thomas Fritta and they settled in Prague. Erna died in 1955 and Haas moved to East Berlin, where he married for a third time (Inge). He worked as the editor of a caricature journal called Eulenspiegel and designed movie sets for the DEFA Company and for East German television. He exhibited his works in East Germany, in Western Europe (France, Italy, Austria), and in Israel, China and the United States.

In 1981 Haas held an exhibition in his birthplace, Klatovy, where he was given a certificate of recognition and honorary citizenship on his 80th birthday. He passed away in 1983.

(Dr Pnina Rosenberg)

References

Beit Theresienstadt (Theresienstadt House) archive, Givat Haim-Ihud, Israel.

Janet Blater and Sybil Milton. Art of the Holocaust. Pan Books, London, 1982.

Mary S. Constanza. Living Witness: Art in the Concentration Camps and Ghettos. The Free Press, New York, 1982.

Gerald Green. The Artists of Terezin. Hawthorn, New York, 1969.

Henryk Keisch. Leo Haas – Terezin/Theresienstadt. Eulenspiegel Verlag, Berlin, 1970.

Miriam Novitch. Spiritual Resistance: Art from Concentration Camps 1940-1945 - A selection of drawings and paintings from the collection of Kibbutz Lohamei Haghetaot. Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981.

Paintings from Terezin: Bedrich Fritta, Karel Fleischmann, Otto Ungar, Peter Kien. The "Lidice Shall Live" Committee, London, no date.

Sabine Zeitoun and Dominique Foucher (editors). La masque de la barbarie: le ghetto de Theresienstadt 1941-1945. Preface by Milan Kunda. Centre d'Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Ville de Lyon, 1998.