Paul Goyard

Paul Goyard's sketches represent some of the few surviving authentic visual documents of daily life in Buchenwald. His work is distinguished not only by its historical significance but also by its artistic merit and documentary approach. The drawings provide detailed insights into the camp's physical structure and the conditions endured by prisoners, created by someone who experienced them first-hand.

Born into a modest shoemaking family in Digoin, Burgundy on December 28, 1886, Goyard's artistic journey began far from the theatrical world he would later inhabit. His early life took a significant turn during World War I, where he served on the front lines until a knee injury sent him to a military hospital. During this period, he produced his first known works - sketches from the trenches and hospital wards.

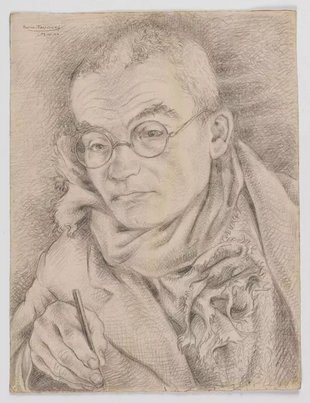

By 1919, Goyard had found his way to Brussels, working in a theatrical scenery workshop. This experience led him to Paris, where he established his own set design workshop. His professional work expanded beyond theatre productions, as he designed scenery for premieres at the avant-garde Théâtre de l'Œuvre. Alongside his theatrical work, Goyard became politically active, creating demonstration placards for the Communist Party and forming connections with prominent artists like Fernand Léger and Boris Taslitzky.

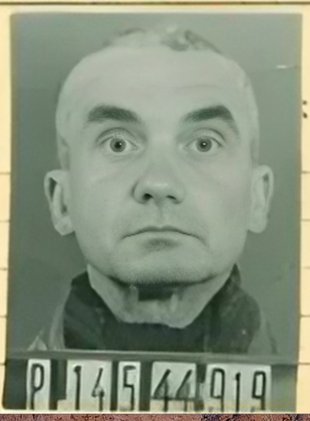

When Nazi forces occupied Paris, Goyard joined the Resistance movement. His political activities led to his arrest in 1942, and on May 14, 1944, he was transported from the Compiègne internment camp to Buchenwald concentration camp, where he was categorized as a "Political Frenchman."

At Buchenwald, Goyard found himself among a group of French and Belgian artists and intellectuals who gathered regularly in Block 34. This group included notable figures such as Julien Cain, Christian Pineau, Boris Taslitzky, José Fosty, and René Salme. Through their mutual protection and resourcefulness, they managed to continue their creative work despite the horrific conditions.

Initially housed in Block 57 of the Little Camp (Petit camp), Goyard later moved to Block 40 in the Big Camp (Grand camp), a transfer facilitated by the camp's resistance movement. His artistic work at Buchenwald was enabled by his assignment to certain labor detachments, which provided him with the protection and opportunity to sketch his impressions of camp life. During his year of imprisonment, he created approximately 300 pencil drawings on scraps of wastepaper, documenting daily life in the camp with unflinching detail.

Artistic Documentation of Buchenwald

Goyard's drawings captured multiple aspects of camp life: the crowded barracks, converted horse stables, makeshift tent accommodations, the crematorium, roll call square, and the physical toll on prisoners, including both the living and the dead. His work stands out for its documentary and formal quality, providing rare authentic visual records of life inside a Nazi concentration camp.

The artistic work of Goyard and his fellow prisoners represented both a form of resistance and an essential documentation effort. Working alongside other artists like Boris Taslitzky, who also produced hundreds of drawings during his imprisonment, Goyard participated in what became a collective artistic testimony to their experiences. These creative activities were necessarily clandestine and were enabled by the solidarity of prisoners and the protection of underground camp organizations.

The style and subject matter of his sketches remained consistent even after liberation in April 1945, though his increased artistic output and broader range of subjects subtly reflected his newfound freedom.

Post-War Life

Upon returning to Paris after liberation, Goyard discovered his workshop had been destroyed during the occupation. Rather than returning to theatre work, he rented a small studio and embarked on an ambitious project with fellow camp survivor José Fosty. Together, they created a detailed diorama of Buchenwald concentration camp, using Goyard's wartime sketches as reference material.

The diorama project represented a unique approach to documenting and sharing the camp experience. Based primarily on five detailed studies from his camp drawings, Goyard created panorama-style preliminary drawings that served as the foundation for the three-dimensional model. The diorama's concept was distinctive in its scope, depicting the camp from the slope at the edge of the Little Camp to the prisoner lodgings in the Big Camp section. This educational tool toured in various exhibitions, though it was ultimately lost. The camp sketches had essentially served as memory aids for this larger artistic project, transforming personal documentation into public education.

Goyard never returned to his pre-war profession as a set designer. Before his death in Paris on March 1, 1980, he entrusted his concentration camp drawings to José Fosty. In 1998, Fosty donated 250 of these drawings to the Buchenwald Memorial. The Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation later published 100 of these works in 2002, accompanied by Fosty's personal account and biographical documentation.

The artistic efforts of Goyard and his fellow prisoners like Boris Taslitzky demonstrated remarkable resilience and resistance within the camp system. Their documentation work, conducted under extreme secrecy and risk, created an invaluable archive of witness testimony. The collaboration between these artists continued beyond liberation, with some working together on post-war projects that further preserved and shared their experiences.

The survival and preservation of these works offer researchers and historians valuable documentation of life within the Nazi concentration camp system, recorded by an artist who managed to maintain his creative practice even under the most extreme circumstances.